Moyo Okediji. Exploring the artistic and computational coding aspects of Ifa

Posted by: Benjamin Onuorah

"Are you a Babalawo?"

I regularly receive this question.

No, I am not a Babalawo.

I am an Ifa scholar and practitioner.

People have assumed that Ifa scholarship and practice is simply about "Awo," secrecy, and spirituality, even religion.

This cannot be further from the truth.

I was 17 when I started the study of Ifa in 1973 at the University of Ife. Our teacher was Dr. Wande Abimbola, who at that time was a Senior Lecturer at the university.

Baba Abimbola, the Awise Agbaye, is now the preeminent voice of Ifa worldwide.

In the early seventies, Dr. Abimbola had just moved from the University of Lagos to Ife, and he offered a class called YOR 001, Introduction to Yoruba Literature.

I had no idea that it was an introduction to Ifa literature when I took that course in a class of only five students.

October 1973, therefore, was actually my first encounter with Ifa.

Though the class focused on the literary aspects of Ifa, it soon became clear to us, as Baba Abimbola continued to teach us, that the content of Ifa was not just literature, performance or spirituality.

The class soon realized that Ifa was the encyclopedia of Yoruba civilization.

There is science, philosophy, music, art, pharmacology, geography, mathematics, computational studies, technology, coding, history, botany, zoology, medicine, geography, rhetoric, counseling, ethics, morality, civics, government, legislation, cuisine, fashion, visual arts and many other forms of scholarship in Ifa studies.

Those who focus on the spiritual and religious aspects are called Babalawo (men) and Iyanifa (women).

I was not particularly interested in the religious aspects of Ifa.

The literary, visual and mathematical aspects of Ifa interested me.

Those who colonized Yorubaland understood the centrality of Ifa within the Yoruba civilization.

They stereotyped Ifa as religion only.

Because they controlled the educational aspect of Nigeria (within which they constrained the Yoruba civilization), they taught Yoruba youths to believe that Ifa had no value beyond the religious.

In just a couple of generations, using the resources of the colonial authority, they successfully spread the propaganda that Ifa, as religion, has no place in the modern scientific world.

The science of Ifa, built on the ecology of Yorubaland, was denied by the colonizers.

They defined “science” in a manner that removed ethics and morality, which is not the way it is defined in Yoruba civilization.

In that civilization, science and technology are practiced as part of the Omoluwabi ethos—meaning that you cannot separate science from the behavior, biography and morality of the scientist practicing the science.

In Ifa, science is regarded as a sociological tool tied to the lives of the people that it serves.

This is why in Ifa studies, what is most important is the moral character and humility of the scientist, technologist, philosopher, musician, artist, pharmacist, geographer, mathematician, programmer, historian, botanist, zoologist, doctor, and creative performer.

Separating knowledge from morality is dangerous.

This is why Western science and technology, powerful as they are, have also brought so much destruction to humanity, putting our planet at the risk of ecological exhaustion, with wars and threats of war spreading all over the world.

Ifa teaches us that “A ki? i? gbo?? bu?buru? le??nu abo?re??.” It means that the Ifa scholars and practitioners are devoted only to the good of the community.

You don’t have to be a Babalawo to be an Ifa scholar or practitioner.

---

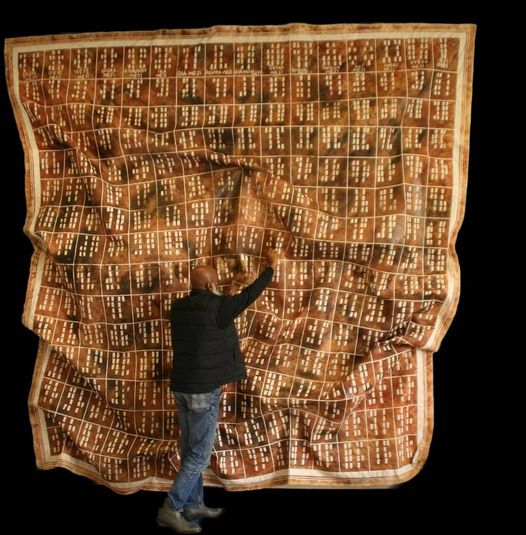

This picture shows me exploring the artistic and computational coding aspects of Ifa.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/100000080640719/posts/8300855203260419/?mibextid=rS40aB7S9Ucbxw6v

Prof. Moyo Okediji

Share:

Comments

No Comment yet!

Professor P. N. Okeke

Echoes of Home: Nostalgia, Memory, and the Quiet Language of Belonging

I’m so proud of you, my son David

Psychology says people who always take notes by hand instead of typing usually possess these 8 distinct traits

The arts and humanities celebrate what makes us human

Someone on Twitter asked why we have so many PhD holders in Nigeria...

Theorizing Nigerian Indigenous Knowledge Systems

The Beauty of Inaugurals

Baba Bruce at 93: A Living Treasure of Innovation and Generosity. By Dr Ganiyu Jimoh Jimga

Do You Sleep At All? How I Manage to Be Productive (Part III)

Do You Sleep At All? How I Manage to Be Productive (Part II)

Do You Sleep At All? How I Manage to Be Productive (Part I)

Professor Inno Ụzọma Nwadike was my academic mentor and father.

Focus on What You Can Control

From Birthday Celebration to Lasting Legacy: How Tunji Bello Built an Auditorium for LASU

"EXPO" TO WRITE COMMON ENTRANCE EXAMS

Re: Called out Igbo professors in the diaspora to start talking more about their research online

My Trip to Nigeria, By Professor Moyo Okediji

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) takes over human roles

Disciplinary Gatekeeping In Nigerian Universities

Showing page 1 of 3 pages [Next] [Last Page]